Whitmire: Nobodyâs blaming Roger Bedford anymore

This is an opinion column.

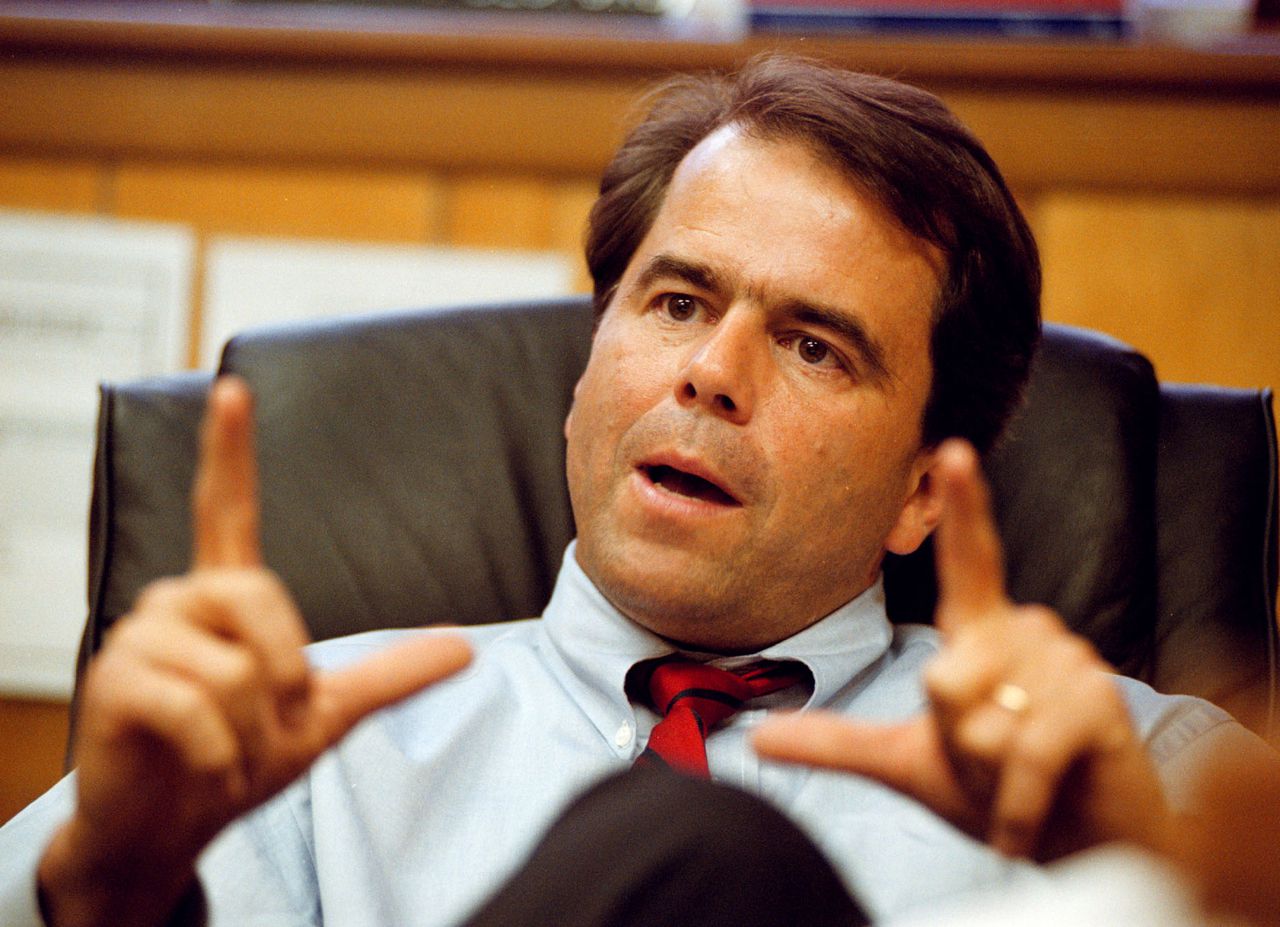

Once Roger Bedford embodied what was supposed to be wrong with Alabama politics — a lawmaker who kept getting elected despite his scandals. Hated by his state but adored by his constituents.

As one of the last white Democrats in the Alabama Legislature, Bedford became Republicans’ biggest target and his political demise was supposed to cap off their statehouse revolution. His defeat was supposed to be a turning point.

It wasn’t.

First, he was gone from the Alabama Legislature, having lost his seat in the state Senate in 2014.

And today he’s gone from this world, having lost a long battle with cancer.

READ: Former Alabama Senator Roger Bedford of Russellville dies

Alabama is still here. Alabama’s not better. Alabama is still broken.

And it’s time to admit, maybe, it was never Bedford’s fault.

A north Alabama lawmaker, Bedford’s influence in Montgomery and at home sprung from his Huey Long style of politics. He spread money around where it suited those he supported, most famously $1.5 million for a fieldhouse at Russellville High School that his colleagues nicknamed the Taj Mahal. Today, after a rainy season of federal COVID money, that might not seem like much, but back then, it looked like a fortune.

Bedford took care of the folks who took care of him. And sometimes, he took care of himself, like when he directed $4,500 of state money for a water line in Wilcox County. The only customer hookup on the new water line was Bedford’s hunting camp.

His campaign expense accounts were a thing to behold, with expenditures for cars and computers. He’s the only lawmaker I’ve seen who dared put the state ABC stores as a vendor on his campaign expense reports.

More than once, Bedford found himself in the crosshairs of corruption prosecutors. In 2003, then-Alabama Attorney General Bill Pryor charged Bedford with extortion, but a state circuit court judge threw out the case three days into the trial.

Republicans laughed with him in the statehouse hall and loathed him on the Senate floor. When they took control of the Alabama Senate in 2010, they tried to put Bedford in a corner.

Bedford embraced his new role in the minority, becoming a contrarian voice and nimble foil for the new GOP majority. During filibusters in the Alabama Senate, he mocked the Republicans for turning into the things they claimed to despise — establishment elites — and he stood up for the groups they attacked, including the Alabama Education Association and the teachers it represented.

For decades, Bedford seemed bulletproof, but in 2014, his political fortunes ran out. He lost his last election by 70 votes to a Florence OBGYN, Larry Stutts.

Bedford’s departure from Alabama politics might be the most revealing moment of his story, emblematic of what has happened in the state in the last 20 years.

Few folks outside of his district knew Stutts, but many cheered when he defeated Bedford.

In one of his first acts in the Alabama Senate, Stutts sponsored a bill to repeal a law named for a patient who died in his care. Rose’s law ensured that women would be tested for a sometimes fatal complication of childbirth and given at least 24 hours to recover in the hospital after giving birth.

Stutts didn’t bother to tell his colleagues about the law’s backstory or his involvement in the case.

Stutts also attempted to repeal a state law requiring doctors to inform women if they had a denser form of breast tissue putting them at a higher risk for cancer. Bedford had sponsored that law, which the Legislature passed unanimously, after his wife battled the disease.

Lawmakers quickly killed both of Stutts’ bills, but the incidents reveal what voters had traded for.

And that’s the story here, more so than Bedford’s direct impact on the state.

When Alabama swapped one political party for the other, things didn’t get better, just different. We assumed different couldn’t be any worse. And we were wrong.

We traded smart, funny and crooked for stupid, mean and stubborn.

Now it’s Stutts who keeps getting reelected, despite his scandals.

And Alabama’s real political problem — like a curse passed from one host to the next — lives on.